[ad_1]

Image credit: James McManus

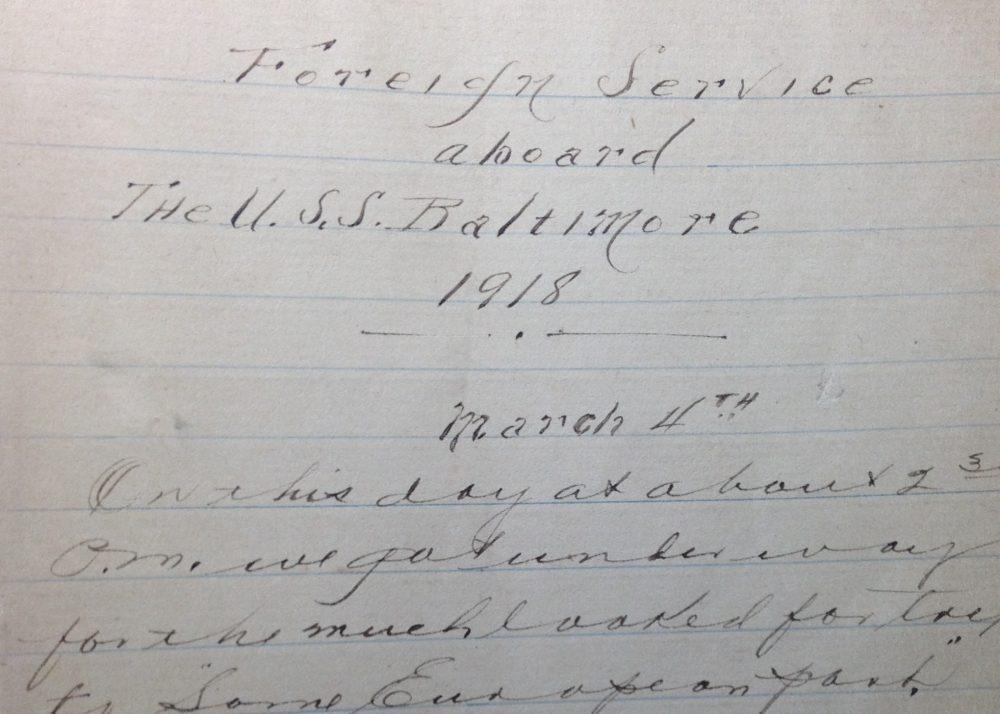

James Laughlin McManus, my grandfather, served as a fireman 1st-class aboard the USS Baltimore as part of the North Sea Mine Barrage in 1918. Their mission was to keep German U-boats out of Allied shipping lanes, and to destroy as many as possible. Grandpa Jim kept a daily journal from March 4 through October 13, usually jotting just a few words but sometimes going on for several pages. On May 1, docked in Lamlash on the Isle of Arran, he writes:

Went ashore in a “Recreation” party for 5 ½ hours. Played base-ball. This is the first time since April 4th that I set foot on the old terra firma.

Planted our fifth load of mines, 185 in all.

This was part a singular celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Baltimore running the gauntlet at Manila Bay, May 1st, 1898.

That’s the first of two dozen entries mentioning baseball games Jim played in or watched while in Scotland. Meanwhile, neither he or his crewmates were aware of the lethal strain of influenza spreading among them. Their youth and testosterone made them the best war fighters but also twenty times more susceptible to the highly contagious new strain of H1N1 influenza, which triggered a violent overreaction by the stronger immune systems of healthy younger adults—unlike COVID-19, which hits older, sicker people the hardest. In 1918 and ’19, this “greatest medical holocaust in history” would cause at least 50 million deaths, more than bubonic plague killed during the entire 14th century.

The “Spanish” flu probably emanated from an army base in Kansas over to Europe on troop-transport ships before mushrooming in the trenches of Belgium and France. Military censorship combined with President Woodrow Wilson’s almost Trumpian denial of bad medical news to make the pandemic longer and deadlier. Wilson’s shortsighted rationale was, “You’re going to war. You’re risking your life. It doesn’t matter if you risk it on the front line or to the virus.” Influenza wound up taking the lives of even more servicemen than the mechanized, industrial-scale combat did.

The virus came close to killing Wilson himself and General of the Armies John “Black Jack” Pershing, Prime Minister David Lloyd George and King George V, as well as Kafka, Walt Disney, Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Katherine Anne Porter (whose dark hair fell out, before growing back white), Mary Pickford, Lilian Gish, Georgia O’Keeffe (whose move from Texas to New York to recover in Alfred Stieglitz’s studio broke up his marriage but helped launch American Modernism), and Edvard Munch, whose “Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu” is a subtler, more finished and emotionally mature painting than the one we call “The Scream.” The virus did take the lives of Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt, Guillaume Apollinaire, American League umpire Silk O’Laughlin, junk-mail inventor Lunsford Richardson, and Queens real estate baron Frederick Trump.

Grandpa Jim probably caught it as well.

![]() (Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1919.)

(Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1919.)

4/5/18

Taken ill with a bad cold and threatened with Diphtheria. Fourth case sent to the Hospital.

4/6/18

Still confined to the Sick Bay. The fellows from the ship have a free-for-all with “Lime Juicers.” A few injured on both sides.

4/7/18

Feeling pretty well. Left Glasgow at 6 p.m. for Greenock.

4/8/18

Started for sea but had to return as mine sweeping device attached to the bow became entangled with anchor chains. Sent diver down to look over the situation, and he became exhausted. Looks like a bad start.

Allowed to leave sick-bay after receiving a “shot” of antitoxin. Feel well, outside of a cold.

Again, it’s not certain he had influenza. We do know that hundreds of his squadron mates contracted it. The 35 nonconsecutive days Jim spent in sick bays, where he was given the shot for diphtheria, suggest that he’d actually caught and survived influenza. The two respiratory diseases had similar early symptoms—cough, sore throat, fever—and were often confused with each other. Diphtheria is a bacterial infection, but the diagnostic tools of that time could only detect bacteria, not smaller pathogens such as the influenza virus. Recent studies also suggest many deaths in 1918 weren’t caused by the virus itself but by secondary infections such as diphtheria and pneumonia. The overwhelming majority of naval victims died stateside, especially men stationed at Great Lakes in Illinois. American sailors on ships operating with the British Fleet suffered much lung-related illness but relatively few deaths, possibly due to better medical care. Jim was lucky to be serving Over There, and maybe for having a weaker immune system than those killed by the virus.

5/7/18

Further operations belayed as the English mine sweepers enter the fields planted by us, and swept about 150 mines. Still they wonder why they haven’t won the war.

Two months into his journal, this is the first example of what we would call snark.

5/8/18

Had a recreation party in the afternoon. Played base-ball and defeated the U.S.S. Gold Sheep 9 to 7.

5/11/18

Recreation. Played base-ball.

What position does he play? Any runs, hits, or errors? Does modesty or embarrassment keep him from saying? And what did he look like? We have no picture of him as a sailor, but the Navy says he was five feet seven and weighed 143 pounds, with gray eyes, brown hair, and a “ruddy” complexion—probably ruddier when fighting diphtheria, the flu, or the U-boats.

(Thomas Hart Benton, Starry Night, 1941.)

5/18/18

Played the Kiowa and defeated them 7-2. Murray starred with his pitching. Molignoni carried off the batting honors. Met Walter Ewart and had a most pleasant time. He is on his way to London to join Sims’s staff.

Vice Admiral William Sims, commander of U. S. naval forces in Europe, was the stubborn old salt Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt had barely managed to persuade that the Mine Barrage could be effective.

5/20/18

Celebrated my twenty-fifth birthday by doing a good day’s work.

6/8/18

Commenced mining at 5:15 a.m. At 5:35 a violent explosion was heard. This was followed by many others. It was learned that the mines were exploding through some defects. The speed of the ships spared them from harm. Roanoke became disabled.

We laid 180 and had two explosions. Was on watch in the engine room at the time. Felt an almost indescribable thrill when the first explosion occurred as I thought we were under fire. Expecting to meet a part of the German Navy at any time.

6/26/18

Baseball game between the San Francisco and Baltimore. Baltimore 6 – Frisco 3. Today completes one year in the service. Commenced training at Newport, R. I. June 1917. Arrived aboard the Baltimore 8/22/17. . . . Left NY 3/4/18 for European waters. During the past year had 15 days leave. Spent 35 days sick in the hospital and at home.

Home was in Providence, a short drive from where he trained.

7/4/18

Today, though far from the good old U.S.A., was spent in celebrating the 142nd anniversary of our Independence. It was an unusual celebration of this great day, for all Great Britain joined us. Here, at this port [Inverness], the battleship Erin of his majesty’s navy had the Stars and Stripes flying aside the Union Jack. The editorials of today’s papers often and fiercely commented on the righteousness of the cause championed by the “Boys of ’76.” . . .

At 9:30 we accompanied the baseball team to the beach and witnessed a very good game, that resulted in a win for the Baltimore. The box score showed Baltimore 8 – Aroostook 1. Murray allowed but one hit. As is customary, almost an hour was spent in practice before the game. During this time, I had the opportunity of seeing recruits to the Scottish Rifles being drilled. There seemed to be no let up on the “rookies.” One of them told me they are trained in six weeks and then sent to France. There would be gas chambers, trenches, barbed wire entanglements and even posts for snipers. The recruits were very young.

Jim the player and fan might not have known this yet, but Thursday July 4 was the day on which a baseball league comprising the best players from each of the twelve U.S. minelayers began to play ball. The schedule would prove to be irregular, because the mission took priority and Highlands weather didn’t always cooperate. Every team couldn’t play the same number of games, so standings were kept in order of winning percentage. Over that summer, 176 games would be contested, an impressive number in a mountainous country of golf links and football pitches, with no diamonds at all until these Yankee bluejackets showed up. By comparison, an Army league in London involved only eight teams and 112 games. Doughboys in France were issued bats and balls, but no league seems to have been organized amid those hellish conditions.

(USS Baltimore, off the coast of New York.)

“In that hit and run game called Mine-Laying, Time means more than Money, and Speed is the Factor of Safety, but Athletics is the Guarantee of Teamwork, and that is the Road to Success.” This longish motto is what the men of the squadron offered as the rationale for their league. And not just any Athletics, but the unchallenged national pastime. In that lively dead-ball era, when home runs were so rare major league leaders, and indeed many teams, finished with fewer than ten, baseball rewarded defense, contact, speed, timing, a knack for the hit-and-run and safely making it home.

***

With the exception of the San Francisco and the Baltimore, none of the planters had the necessary baseball equipment, but that couldn’t put a damper on the sport. When the schedule had been arranged, baseball diamonds were ready at Inverness and Invergordon, and the required equipment was being rushed from the States. . . . [E]ach team was supported by as loyal a group of fans as ever downed an umpire. It was a hot race from start to finish and the keenest sportsman-ship prevailed throughout, as can be evidenced from the present battle-cry of the Scotchmen of Inverness and surroundings—“Baseball forever.”

The standing of the teams:

| Ship | Games | Won | Lost | Pct |

| Canonicus | 20 | 13 | 5 | .750 |

| San Francisco | 17 | 12 | 5 | .706 |

| Housatonic | 18 | 12 | 6 | .667 |

| Black Hawk | 16 | 9 | 7 | .563 |

| Roanoke | 13 | 7 | 6 | .538 |

| Baltimore | 14 | 7 | 7 | .500 |

| Shawmut | 18 | 9 | 9 | .500 |

| Aroostook | 13 | 5 | 8 | .384 |

| Quinnebaug | 14 | 5 | 9 | .357 |

| Cannadigua | 15 | 4 | 11 | .267 |

| Tugs | 4 | 1 | 3 | .250 |

| Saranac | 14 | 3 | 11 | .214 |

It was estimated that 3,000 townspeople were present at the Northern Meeting Grounds in Inverness to see the big games of the Mine Squadron at Base 18.

***

7/5/18

Received mail from the States. Wrote a piece for “Fleet Review.”

The short piece, his first publication, took the form of a letter to the editor of this widely read monthly, which didn’t run it until the September issue, ghastly timing for Jim, as we’ll see.

Baltimore Still Full of Pep.

U.S.S. Baltimore,

U.S. Naval Forces, Europe,

U.S. Naval Base 18.

EDITOR THE FLEET REVIEW.

Without conforming to the time-honored custom of telling you how much your magazine is enjoyed by the ship’s company, I shall proceed to narrate a few of the many interests that make the Baltimore the most-talked-of ship in European waters.

In the first place, she had the distinction of being the first ship of her division that arrived in these parts and immediately set to work to make the world free from autocracy. It is regretted that no details can be given, but when the deeds of our Navy have been written, the present work will outshine her great feat at Manila Bay, when she was supposed to be at the zenith of her glory.

Regardless of the task at hand, we put a baseball team on the diamond that has proved invincible. A dozen victories have been won without suffering a single defeat. Without any trace of egotism on the part of the ship’s company, you can hear them boast of the accomplishments of their star twirler, Jim Murray. His fame has preceded him to many a port where the Baltimore is spoken of.

Looking over the records of this year, we find that he is credited with eleven victories in as many starts. On one occasion he allowed but one hit, which happened in the ninth inning. Very recently, on one of his “off days,” he was on the firing line for eleven innings. During that time he struck out twenty-two men and allowed five hits. Uncle Sam’s gain was the big league’s loss. Cofty and Neurer, our catchers, have discouraged many an ambitious young man who tried to pilfer second. Lieutenant Thornhill plays the initial sack. For further information as to his prowess in the national pastime consult the Naval Academy records. Elmer Smith, at second, is a second edition of Eddie Collins. Molignoni, at short, is all that you could expect of a ball player, both at bat and at fielding. “Pop” Blesso tends to the “hot corner.” His timely hitting and faultless fielding has made him the favorite, not only on his own team, but with all who have watched him perform. “Babe” Bennet, who pastimes in left field, has broken up more ball games with his “big stick” than any man in the service. Reuter, in center, is one of the most consistent players who never attract much attention, but have the happy facility of hitting in the pinches. “Hook” Nahrwold is giving Bennett a “run” and covers more ground than the fans ever saw. Our “royal rooters” have sent many a pitcher back to the showers long before the game was half played. . .

After giving the foregoing the “once over,” you can only and rightly conclude that the crew of the Baltimore is full of “pep” and keeping the standard set by those who helped to immortalize her in naval history.

With only good wishes for your continued success in bringing before the personnel of the Navy your many and interesting suggestions through THE FLEET REVIEW, I remain,

J. L. McManus.

***

If this sounds like public relations copy from a ballclub’s own hey-get-yer-program, some context is in order. From the earliest days of baseball, in the 1830s, correspondents were prone to hyperbole, in what historian R. Terry Furst calls “a colorful but exaggerated style of prose.” On May 20, 1875, a notice appeared in the Hartford Courant:

“TWO HUNDRED & FIVE DOLLARS REWARD—At the great baseball match on Tuesday, while I was engaged in hurrahing, a small boy walked off with an English-made brown silk UMBRELLA belonging to me, & forgot to bring it back. I will pay $5 for the return of that umbrella in good condition to my house on Farmington avenue. I do not want the boy (in an active state) but will pay two hundred dollars for his remains.—Samuel L. Clemens.”

Master humorists aside, Baseball Hall of Fame writer Harry Chadwick, who invented the box score in 1859, often complained about profligate writing, calling out prose that put “the blood-and-thunder dramatists and yellow-covered novel writers into the shade.” He was most offended by this gaudy amethyst by a Cincinnati reporter: “Every base was full. George Wright stepped to the bat amidst a stillness as of death when the ‘boldest held his breath for a time’ to make the run . . .”

Despite Chadwick’s chagrin, men covering baseball maintained their license to write more flamboyantly than other journalists. What harm could come, after all, from a stretch of purple sentences describing a ball game? Many scribes became celebrities in their own right with styles more amusing than factual. Exhibit A was Mark Twain, the most famous American of his time, who wrote about everything. Editors bid up the salaries of the most popular writers, incentivizing others to follow their stylistic lead.

Baseball teams were also a source of civic pride, especially after the World Series was launched in 1903, and a similar pride was at stake when teams from navy ships competed against one another. Since before the Civil War, the national pastime had been a source of communal bonding, which only intensified when the country was at war once again, this time as 48 states united against common enemies.

Writers such as Grantland Rice and Red Smith became famous for hyping athletes as mythic or godlike. Rice’s “Four Horsemen” analogy might be the most notorious. “Outlined against a blue-gray October sky the Four Horsemen rode again,” he would write in the New York Herald Tribune in 1924, about a football game between Army and Notre Dame. He was only warming up for a colossal mixed metaphor. “In dramatic lore they are known as famine, pestilence, destruction and death. These are only aliases. Their real names are: Stuhldreher, Miller, Crowley and Layden. They formed the crest of the South Bend cyclone before which another fighting Army team was swept over the precipice at the Polo Grounds this afternoon as 55,000 spectators peered down upon the bewildering panorama spread out upon the green plain below.”

Apocalyptic horsemen. Famine and pestilence. The crest of a cyclone. It all makes J. L.’s prose seem downright fact-bound or vanilla. Meanwhile, Red Smith’s editor, irked by a gushing piece Smith filed about Joe DiMaggio, told him to “stop goding [sic] up the athletes.” He wouldn’t.

I almost wish the same editor had ridden herd at The Fleet Review in 1918, encouraging in Jim a plainer allegiance to reality. Yet would such guidance have shrunk or lengthened the odds he would write about sports for a living? He hoped this could happen, and maybe he thought lavender blarney was the ticket. He didn’t know it then, but in the early ‘20s big urban newspapers began devoting many more pages to sports, so with two clips in hand a salaried writing job may well have been in the cards.

Yet Jim wasn’t off-base at all when he reckoned, after watching Big Jim Murray work his southpaw magic, that major-league clubs could have used him. Murray went on to pitch for the ’22 Brooklyn Robins, as the Dodgers were called then, compiling a 4.50 ERA and 1.833 WHIP over four games as a mop-up closer. That was it. At 27, he could have been past his prime. The dead-ball era was over, mostly thanks to Babe Ruth, when Murray pitched for Brooklyn. It’s not clear whether injury or substandard stuff limited him to four appearances. At six-foot-two, 240, the same size as Ruth, he was huge for that period. His length helped him whiff amateur batters in the Navy, at least those on the weaker teams he faced before July. He was effective pitching for Syracuse University right after the war, but proved average at best against big-league hitters. He had probably been as dominant as Jim suggests, but going nine-plus innings twice a week in Scotland, then in college, wore out his arm. It was his tough luck to have played almost a century before five-inning starts and Tommy John surgery prolonged many pitchers’ careers. Murray missed the ‘23 season, likely due to injury, and spent the next two trying to prove himself again by pitching for minor-league clubs, before retiring at age 31.

(selection, journal of James Laughlin McManus.)

7/7/18

Baltimore defeated the Quinnebaug 9-2.

7/10/18

Baseball game between Baltimore and Shawmut. Baltimore 6, Shawmut 5 (11 innings). Murray allowed six hits and had 22 strikeouts.

7/14/18

Started for the mine field at 11:30 a.m. Were accompanied by nine other mine layers. We had twelve destroyers and four battleships for protection. Saw the wreck of a British cruiser that was destroyed by an internal explosion in 1916. Enemy air machine sighted.

7/15/18

Commenced planting at 10 a.m., and the last one went over at 3 p.m. About 7,000 in all. Many violent explosions occurred like on our previous trip.

7/20/18

Baltimore team defeated the Housatonic 3-2. Went to a show in the evening. Got drenched returning to the ship.

Drenchings and rainouts were common. As far north as Juneau, Inverness averages almost 18 hours of daylight in July, but it rains on 18 of the 31 days. Highs range from 63F to 65F, seldom exceeding 72. It was even cooler in 1918.

7/24/18

Baltimore team was defeated by the Roanoke 4-1. Received mail from the States.

7/27/18

Baltimore team defeated by the Black Hawk 6-5. Captain inspection.

7/30/18

The sea was very rough, so much so that the mines kept moving on the tracks. I had my first experience with seasickness. Commenced mining at 8:15 a.m. Many explosions took place. Some were dangerously near. About 7:15 p.m. a trawler that was perhaps 2,000 yards off our starboard side dropped a depth charge on a submarine. Anchored at 7 a.m. 7/31/18.

8/1/18

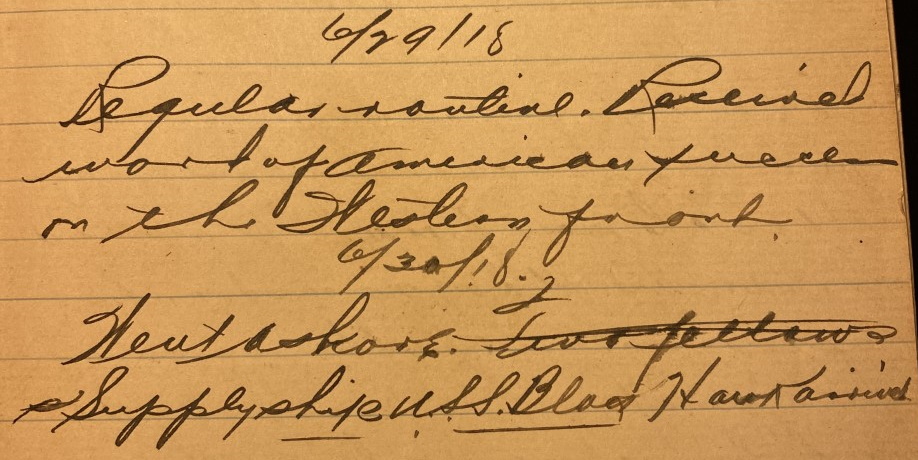

Regular routine. Wrote a piece for the Mine Force Semi-Monthly.

I’ve yet to track this one down, or find even a single mention of what can only be called a niche periodical. The season is now in full swing, and minelaying details were classified, so my guess is that this piece too was on baseball. If so, Jim would have been wise to tone down the dominance he’d earlier ascribed to the Baltimore team, as it slumped toward its eventual .500 record.

8/5/18

Had the afternoon off. Skipper makes known that he is strong for base-ball and has only his interest in the crew’s welfare.

Captain Albert Marshall must have caused a game to be postponed by taking a longer route back from a mining excursion, perhaps to avoid U-boats detected along their usual path home to Inverness.

8/7/18

Baltimore defeated by Canoniers 15-2. Took 180 mines aboard.

8/17/18

Baltimore defeated Frisco 4-0. Murray allowed 2 hits and had 14 strikeouts. Crew won $4,000.00.

Turns out Jim’s crewmates were betting long money on these games, on this one alone a sum equivalent to $70,000 today. All 368 men wouldn’t have bet, since Article X of the Regulations prohibited gambling at “stations belonging to or under the control of the Navy.” It’s unlikely that Catholic teetotaling Jim risked even one thin Liberty dime; had he bet, he would have said so in his journal. But if, say, half the men divided this $4,000 payoff, a typical wager would have come to over two weeks’ pay on just one of the 14 games played: $25 bet per man, average pay around $50 per month. Whatever the precise numbers were, these minelayers were betting like, or as, drunken sailors.

8/29/18

Canandagua defeated the Baltimore 7-6. No one went ashore with the team.

Because they had too much work to do, coaling the ship or taking on mines? It’s likely that no extra shore leaves were granted because Navy brass feared the further spread of influenza, rampant by now among British and American crews.

9/2/18

Labor Day. Had games. Frisco defeated Baltimore 17-2.

The September issue of Fleet Review is out now, and Jim’s star-spangled assessment of the Baltimore nine undoubtedly cost him some ribbing, at least from the crew of the Frisco. “‘Invincible,’ huh?” “Sounds like ‘J. L.’ got his signals crossed.” His only satisfaction would come from not losing dough on the blowout and, far more gratifying, finally seeing his pen name in print, an experience he wanted to repeat.

***

Back in the States, Secretary of War Newton Baker had ordered an abrupt end to the major-league baseball season, already shortened from 154 to 140 games “on account of war.” Many players were now sick or quarantined. Outfielders, even retired players, had to come in and pitch. After Baker ordered all men under thirty to “work or fight,” two in five major leaguers entered the military. Cincinnati manager Christy Mathewson, 38, enlisted as a captain in the defensive Chemical Warfare Service, along with St. Louis manager Branch Rickey and Detroit centerfielder Ty Cobb. As the ever-loving Damon Runyan had written of Mathewson’s greatness as a pitcher for the Giants: “Mathewson pitched against Cincinnati yesterday. Another way of putting it is that Cincinnati lost a game of baseball. The first statement means the same as the second.” In France, after helping to sell more than $100,000 in war bonds in a single day, Mathewson was accidentally gassed during a training exercise. His damaged lungs made him susceptible to tuberculosis, which took his life seven years later.

There were many ways to die in this war.

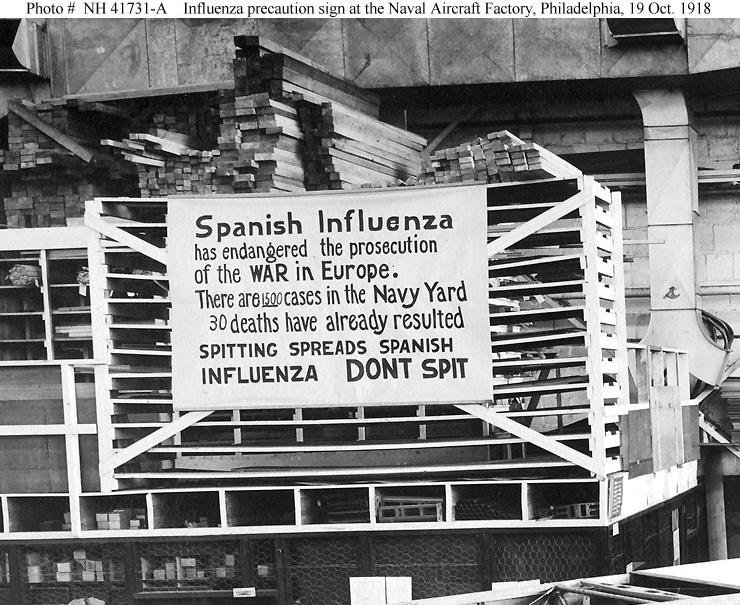

Anticipating an MLB rule from our Covid-plagued seasons, the Navy Yard in Philadelphia posted big signs.

By September 2, the pandemic was so rife and deadly it threatened to cancel the World Series between the Cubs and Jim’s team, the Red Sox. Troops passing through the port of Boston made it an epicenter of the disease, though Wilson’s hardline propaganda and unprecedented degree of censorship kept the public from knowing how bad it was. With “a war to end all wars” going on, few in the press dared to push back.

Furious disputes about gate-receipt splits with the players also put the Series in jeopardy, but play it they did. After shutting out the Cubs in the opener, Babe Ruth won Game 4 as well, 3-2, picking speedy Max Flack off second and tripling home the game-winning run. (He’d also bashed 11 of the 12 homers his team hit that season.) On what turned out to be the last morning of the Series, September 11, Boston health commissioner Dr. William Woodward finally defied his own deceitful president by warning citizens to avoid “crowded cars, elevators, or buildings.” Only 15,238 showed up at Fenway Park to watch the Sawx clinch the championship. No victory parade ensued.

While the raw scores were reported by radio, detailed newspaper coverage didn’t reach Scotland for days, but was avidly read. An uncredited staffer for the New York Times began, “When Max Flack made a ludicrous muff of Whiteman’s line drive in the eighth inning at Fenway Park this afternoon, two runs wafted over the plate, which gave the Red Sox the baseball championship of the world.” Praising Boston’s infielders, he wrote, “Play after play was ripped off this afternoon when the players seemed to be under the spell of sorcery.”

In the Globe, Edward Martin filed this:

“It was a ball game that nobody who was present will forget. It left too many lasting impressions. True enough it was lost through a muff, but there were so many sensational plays before the contest was finally decided that maybe in the days to come the fan family, taking a look back, will not dwell too long on how little Flack faltered, but will recall how Whiteman, the sun-kissed and sincere Texan, Jackie Thomas and the somewhat elastic Stuffy McInnis thrilled them in the last act. . . . Not too much can be said of the determined little Whiteman. The way that he came through from every angle in the series made the gent that declared that youth must be served take it on the run. . . . His catch off pinchsmith Rollie Zeider in the eighth inning yesterday was one of the best ever observed in a World’s Series. He came in like 60 for a hard-hit ball and plucked it, his own momentum causing him to turn a complete somersault, but he came up with the ball, a smile and wrenched neck, and later had to retire, G. Babe Ruth being provided with an opportunity to make what may be his last bow before those who love to see him bust ‘em. . .

“The last play of the final professional combat went from Shean to McInnis, Stuffy holding up the ball, which was hit by Mann with glee, as the fleet Les was running it out for all he was worth. Then Hooper, Ruth, Mays, Shean, Schang, Scott and others did a fadeout, down came the curtain and from out of the stillness that swept over the battleground . . .”

This was all well and good, but sun-kissed and sincere? Hit with glee?

As we’ve seen, J. L. McManus has already filed, as a rookie, home-team-friendly prose of this caliber, on spec, under less than ideal writing conditions. With a little seasoning, he could surely hold his own on the staff of some broadsheet, especially as the number of sports pages multiplied after the war. Anyway, that was his plan.

***

Germany and her allies surrendered on November 11. Most of the decisive battles had been fought in France, but the Mine Barrage too had been crucial. Combined with the British Navy’s surface blockade, the barrage limited U-boat access to Atlantic shipping lanes, keeping the Allies supplied while cutting off the Central Powers from food and other necessities. Of the 70,113 mines in the barrage, American ships laid 57,470. Mining the North Sea didn’t compel Germany’s surrender with one or two gloriously decisive sea battles, but there’s no doubt it shortened the war.

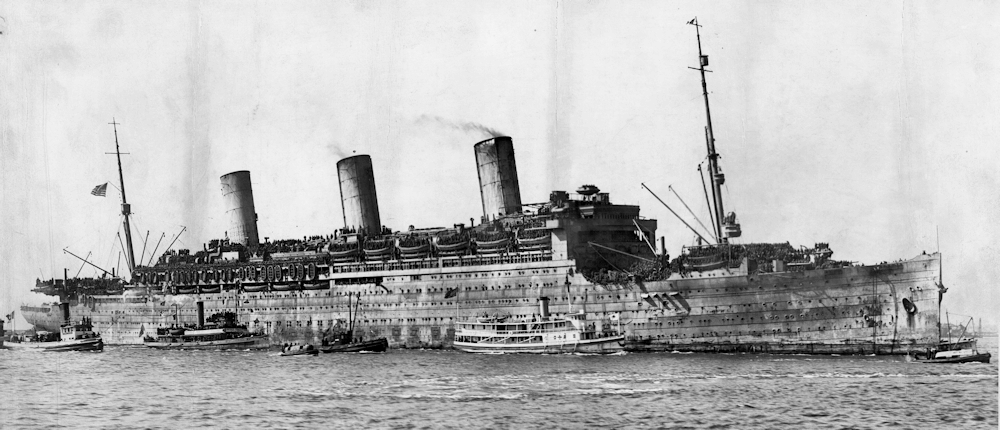

Even so, millions more people from both sides perished in a second wave of flu as they made their way home. They included many hundreds of Americans aboard the USS Leviathan, the world’s largest ship, which back in March had escorted the Baltimore from New York, zigzagging through various U-boat zones to the Inner Hebrides and finally Lamlash. Her crew of 1,300 included helmsman Humphrey Bogart. Rejected for Navy flight school, “Hump” became a model sailor, spending most of his time at sea ferrying soldiers and nurses home from Brest. He described the Leviathan as—hear the voice—“a big bastard, a three-stacker with forty-eight coal burners.” Hear it again as he calls baseball “my game. Ya know, you take your worries to the game, and you leave ‘em there. You yell like crazy for your guys. It’s good for your lungs, gives you a lift, and nobody calls the cops. Pretty girls, lots of ‘em . . .”

(The USS Leviathan.)

Franklin Roosevelt, a friend of Bogart’s parents and a man for whom Bogie later campaigned, also cruised home aboard the fourteen-deck 950-foot colossus painted with a zebralike “dazzle” camouflage. The Assistant Secretary had been urged by his Uncle Teddy to conduct a needless inspection tour of Europe. Embarking from the long pier at Brest, he didn’t know the swift, stealthy, once posh Leviathan had become a kind of plague ship because so many troops were now dying of the flu in her overcrowded bunks and makeshift hospital. Ensconced far above them in a private stateroom, Roosevelt still contracted the virus and barely survived it.

J.L. McManus—eleven years younger than FDR, six years older than Bogart, nineteen months older than Ruth—survived the Great War and the flu to become…a bookkeeper for Steinway & Sons. He soon had a wife, Grace Lynch, and two sons, Don and Kevin, with a mortgage on a house in Mineola, so his dream of becoming a sportswriter would have to be belayed. But in August of 1928, at the age of 35, he died of a heart attack, possibly an aftereffect of the flu. His younger son, Kevin, my father, was ten months old.

Having served twenty months, Jim had been honorably discharged from the Navy early in 1919. The other options being “undesirable” and “inaptitude,” his character was rated “good.” On a scale of 0-4 (“0, Bad; 1, Indifferent; 2, Fair; 3, Good; 3.5, Very Good; 4.0, Excellent”), he was given these grades: “Seamanship, 3.0; Ordnance, 3.0; Signaling, 3.0; Marksmanship, small arms, xxx; Mechanical Ability, 3.3; Knowledge of marine machinery, xxx; Ability as a leader of men, 3.1; Sobriety, 4.0; Obedience, 4.0; Average standing for term of enlistment, 3.3.”

So. Many decades before grade inflation, he was almost very good. Like every adult under 40 not killed by the flu, he was lucky, at least for a while. He was also, like everyone who served Over There under fire, a minor-key hero. No future movie star or president, no hard-drinking gambler or dominant southpaw, but a man to respect and look up to. And a fledgling sportswriter on top of it, at least for one busy and brisk Scottish summer.

(James Laughlin McManus, 1925.)

—James McManus is the author of Positively Fifth Street and ten other books. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, New York Times, Boston Globe, Esquire, Harper’s, The Atlantic, Grantland, and Best American anthologies of poetry, sports writing, political writing, magazine writing, and science and nature writing. He was born in the Bronx and has taught since 1981 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

[ad_2]

Source link